Three points

to note about investment advice that generally floats around:

- Market movements almost never mirror reality/logic, contrary to what theories such as “Efficient Market Hypothesis” will tell you. As Keynes once remarked “Markets can remain irrational far longer than you or I can remain solvent”

- Analysis always tends to be post facto. Therefore, with the wisdom of hindsight, past events may be justified. But there’s no guarantee that future events will play out similarly.

- Most brokers (in the garb of ‘experts’) are paid to peddle stocks on business news channels by certain investors. Use your judgement before committing capital based on hearsay!

We

invest in equities to make superior returns on our capital (vs fixed deposits

and bonds). There’s greater risk obviously, but we hope our insights/information/luck

will help us get to those superior returns. Aim of this post is to analytically

think through what the drivers of those returns are and how the math behind it

works.

Drivers of Returns:

There

are four aspects that primarily move the needle on returns, and all of our

investment diligence should therefore be centered on these issues:

1) Growth: Splits out into market growth

and market share. Say a market is growing with India’s nominal GDP (15%), and

you think the company can gain some share over time (a nuanced sub-segment level understanding of each of the product lines

of the company is necessary to make this claim!) You assume that the share gain

will be rapid and you underwrite that it would outpace the market by say four points.

Implicitly your revenue growth assumption is 20% (16%+4%).

In the

ideal world, you want to find a company that has some of the following

characteristics (obviously non-exhaustive) to give you comfort about growth

& share:

- Strong competitive position in a high-growth industry driven by high barriers to entry (say technology / patents) and brand loyalty (e.g., iPod)

- Scalable business in a concentrated industry that would see a small subset of players capturing an unfair share of the market growth going forward (e.g., 2 wheelers)

- Relatively free from regulatory hurdles and govt/political influence (therefore keep off infrastructure, real-estate etc)

- Low customer churn with long-term sticky contracts (e.g., BPO) or low customer concentration (e.g., retail industry)

2) Margin: You have to take a call on

COGS (Cost of Goods Sold i.e. direct costs attributable to the production of

goods or raw material costs +conversion/direct costs) and SG&A (Selling, General

& Admin expenses). These two are your main cost buckets that flow through to

your EBITDA.

EBITDA

stands for Earnings before Interest, Tax, Depreciation & Amortization. When

people talk about “operating margin”, they refer to EBITDA margin. EBITDA = Revenue

– COGS – SG&A. Other costs below EBITDA are depreciation & amortization

(both are non-cash expenses), interest on your debt (if any) and taxes. EBITDA – Depreciation & Amortization – Interest – Tax = Profit after Tax or PAT.

Now

that we have the definitions out of the way, you should pay close attention to

how you think gross margins (Revenue less COGS) will play out in your

investment period. Say you assume it will improve due to price increase (basic

inflation + price premium for your products due to better perceived quality)

and lower conversion costs. Say you assume you would gain 0.5% of revenue each

year on gross margins on account of these two levers.

You

also have to consider SG&A – you could get some leverage from employee

expenses, better utilization of facilities etc but could consider increasing

spend on sales & marketing. In our case, let us assume all the savings from

the former is invested in the latter (i.e. sales) and your SG&A margin

remains constant every year.

Therefore,

in this case, your EBITDA margin will expand by 0.5% every year (0.5% increase

due to gross margin expansion and no change in SG&A)

3) Multiple: The multiple on EBITDA or PAT is technically meant to be the closest proxy for future cash flows of the company. In reality though, it changes every minute as expectations change depending on macro environment, regulatory changes, liquidity, significant events at other companies etc. To evaluate the “right” multiple to pay, it’s probably wise to compare the current multiple to the five year average to get a sense on how the multiple has moved over time. In the ideal case, you don’t want to be buying off a high. Remember the age-old truism “Buy low, sell high”.

Super-normal

returns can be made if you believe that the market is currently under-valuing

the company and you have sound reason to believe you are seeing something that

the market isn’t and that the market will hopefully come around over time. Many

industries have re-rated upwards (e.g., consumer) and many have re-rated downwards

(e.g., Mid-tier IT) over time, so it is crucial that you see today’s multiple

in perspective and take a call suitably.

In

general, market-leaders trade at a slight premium, so if you believe your

company (say currently at #2) will eventually be #1 due to superior product

innovation, better management etc, you could underwrite a click or two of

multiple expansion. Nonetheless, this is one area where you would rather be

conservative and wait to buy when there’s a steep correction due to an

uncorrelated event.

4) Changes in capital structure: This is a slightly more complex topic and deals with capital structure of a company. It is rarely a driver of returns in India (given high interest costs, regulations etc) so I’m not in favor of a lengthy discussion. But here’s the short of it, for those who are interested:

Say a company

in the US is worth $1B and it’s debt to equity ratio is 4:1 i.e. $800M of debt

and $200M of equity. You use the company’s current cash flows to pay down say

50% of the debt in your investment horizon. Even if the company’s enterprise

value remains constant and nothing else in the business changes materially, you

are now left with $400M of debt => $600M of equity i.e. 3x return on your

equity simply via debt pay down :) This math gave birth to the LBO industry.

Let us

put what we have learned to good use and do some simple math.

Basic math on how returns work:

Say a

company has year-end revenues of Rs. 100, EBITDA % of 20% and PAT % of

10%.

For the

sake of simplicity, let us value the company on LTM (last twelve months) Price

to Earnings (PE) multiple and say the multiple is 15x. Market cap of the

company = 15x PAT = 15 * 10% * 100 = Rs. 150

Now

say there are 15 shares of the company. Therefore, each is valued at Rs. 10.

You buy say 5 shares from an existing shareholder (technically a ‘secondary

purchase’). Now you own 5/15 shares i.e. 33.3% of the company.

Say

five years down the line (typical time-horizon for a long–term investor), the

company has grown its revenues at 20% CAGR and has been able to maintain EBITDA

and PAT margins (over-simplistic, but let us go with this). Assuming the

multiple doesn’t change, you would make 20% returns YoY on your 5 shares. Your

Rs. 50 now is worth 50*(1+20%)^5 = Rs. 124. Therefore, you have a Multiple of

Money (MoM) of 2.5x and an IRR of 20%. Simple?

Let us flex

the other variables as well, so everyone has the math clear in their heads:

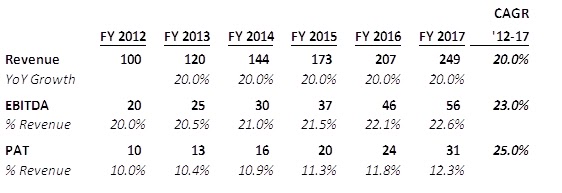

Say the

company’s revenues grew at 20% YoY. Let us now say that the company did a bunch

of operational improvements thereby enhancing its margins and say its PAT grew by

25% YoY. Also assume that the market starts loving the company and starts

paying a premium on its shares, now the multiple expanded from 15x to 18x. What

returns will you make on your 5 shares purchased @ Rs. 10 each?

The

simple P&L will look something like this:

Therefore

the company’s PAT at exit is Rs. 31, the multiple at exit is 18x, therefore market

cap at exit = Rs. 31 * 18 = Rs. 558, up from Rs. 150 at entry.

Share price is now Rs. 558/15 = Rs. 37.2. You own 5 shares, hence your

shares are now worth Rs. 37.2*5 = Rs. 186

Therefore,

your simple returns are:

MoM =

186/50 = 3.7x

IRR =

3.7^(1/5)-1 = 30%. Neat! :)

Note: This return math

assumes none of the following have happened in the investment horizon - dividends/re-caps from excess cash accrued, management options,

interim primary infusion, back-leverage and all other second order issues

I will

(hopefully soon) come up with a separate post on “Nuances to investing in India”

where I will talk about promoter/governance issues, issues with ‘control

transactions’ in India, how bankers try and raise expectations etc.

If you’ve

reached this part, I am assuming you read the post and I hope this was helpful.

I have tried to keep it simple, but if you have any questions, I’m happy to

answer them. You can reach me at utsavmitra@hotmail.com